Between Wonder and Overload

(a free text and thoughts about trust, digital art, and the fragile balance between creation and manipulation)

Jakob Kudsk Steensen, The Song Trapper (2025) — immersive installation of moving image, virtual performance and spatialised sound at Fondation Louis Vuitton. Courtesy of the artist.

Can we trust every artist who opens dimensions through digital art?

To open a dimension in art might mean expanding reality, creating something that no longer needs canvas, paint, or a physical room. The digital world gives artists the freedom to shape everything that exists and everything that does not. It is a boundless possibility, but also a danger. Because just because one can create anything, does it mean that everyone should?

I believe there is a risk in technology giving too many people the ability to express everything in their minds without filter, purpose, or care for the collective. In the past, art required patience, skill, and intention. Caravaggio did not paint just to experiment, but to say something larger about being human. Digital freedom may make creation easier, but it can also remove the shared consciousness that connects art, history, and human experience.

Perhaps that is why I feel resistance toward exhibitions like The Song Trapper by Jakob Kudsk Steensen. Not because the work itself is bad, but because it represents a shift, an eagerness to overwhelm the senses rather than invite reflection. Many museums now seem to chase the immersive, the spectacular, the digital. But is it truly wise just because it is possible? Maybe we should wait. Choose carefully.

When the digital dimension begins to feel as real as the physical one, we are no longer facing just a new art form, but a new reality. And the question is no longer whether we can trust the artist, but whether we can still tell the difference between art and reality once the line disappears.

Ownership of the Experience

When an artwork exists only digitally, the question of ownership becomes blurred. Who truly owns the experience? Perhaps no one, or perhaps both. Art, after all, is a meeting, a shared exchange between the one who creates and the one who receives. The artist opens a space; the viewer steps inside. Art lives in that encounter, and thus it can never belong entirely to either.

Yet this comes with responsibility. The creator must understand that there is no single way to experience a work. Some will feel deeply, others barely at all. This has always been true, but in a digital reality where illusion and truth intertwine, that responsibility grows heavier. When illusion becomes as tangible as reality, it is no longer just art, it is world making.

Art has always been a mirror, but it is also a window to the past, the present, and the future. It does not only show what is, but what could be. Artists reflect their faith in the future, their longing for it, or their fear of it. In a time when digital worlds are expanding, art becomes both a portrait of the future and an echo of our collective belief in what is real.

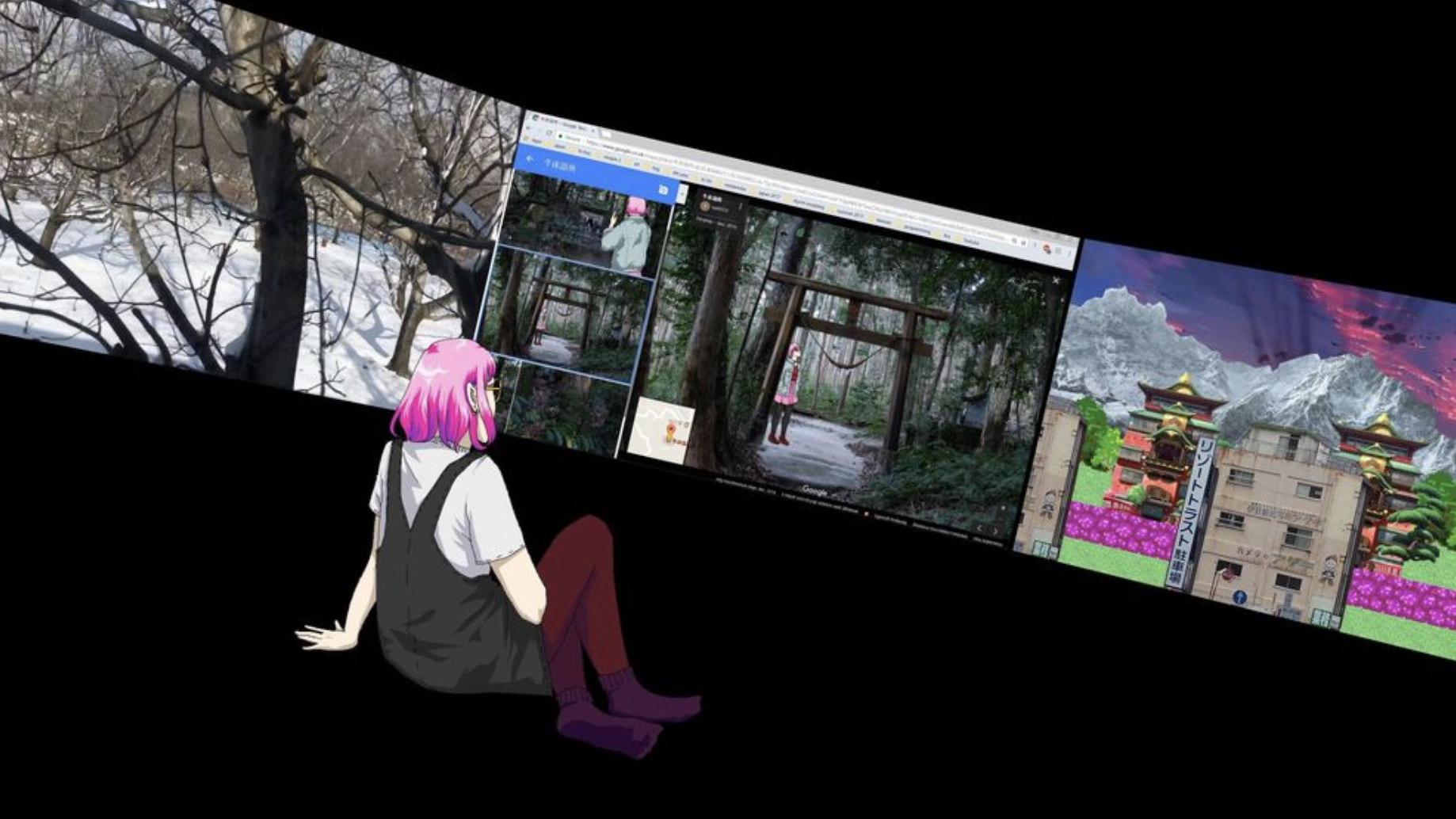

Bjarne Melgaard, My Trip (2019) — virtual reality installation exploring the far reaches of the web and our tech-driven consciousness. Source: Acute Art.

Technology and Soul

Does digital art have a soul, or merely an echo of human consciousness? Perhaps both. It comes from us, from the artist’s subconscious impulses and conscious choices. And if humans have souls, then so does art. Digital art is an echo, but not an empty one. It carries the imprint of human thought and the intention behind the code.

Even in a world made of algorithms, there is still room for error, improvisation, and chance. Artists can still fumble, experiment, and fail, and in that something alive emerges. Technology can be a medium, but it is still the human who breathes meaning into it. Asking whether the artist is human or machine may be the wrong question; it is not about who creates, but what happens in the encounter.

Can AI be an artist? Maybe. It can open dimensions, create, and communicate. But it still takes human experience for art to feel real. Art becomes real only when a person meets it, sees it, feels it. Without the viewer, there is no reality, only potential.

And perhaps it is not new to feel something from something that does not physically exist. We have always done that, through film, through music, through games. The only difference now is that the boundaries blur further, and we must ask again: where do we end, when there is no clear line between the human and its shadow?

Trust and Power

When we give our trust to an artist, we surrender a small part of our control over how we see the world. Art always influences us, but in the digital age, that influence becomes more immediate, more immersive, more total. Through VR, AR, and virtual worlds, artists can now create realities that feel real. That is a tremendous power, and one that institutions still struggle to fully understand.

Many museums seem mostly eager to appear current, to prove that they are in touch. They open their doors to everything that looks innovative or technologically advanced. But have they truly reflected on what they are exhibiting, or to whom they are granting trust?

It is fascinating to see how artists use technology, but also unsettling when it happens without intention or care. Who takes responsibility when a virtual experience alters how someone perceives themselves or the world? The curator’s role should be to ask those questions, not just to be dazzled by new tools, but to consider what is being communicated through them.

Trust, after all, is a form of power. To grant an artist the space to shape the public’s perception is to give them influence, perhaps more than we realize.

Between Art and Manipulation

Where is the line between art and manipulation when the experience is digital? When we trust an artist, we allow them to affect how we think, feel, and perceive reality. In a physical space this happens indirectly, but in a digital one, it can happen through our senses, almost beneath our awareness.

When anyone can use digital tools to express anything, there is also the risk that art does not just communicate, but manipulates. An artist can, consciously or not, project their own inner chaos outward, and we as viewers become exposed to it. That is why it may be necessary to ask a simple but vital question before entering any digital work: Who have I just given my trust to?

That trust becomes part of the artwork, an invisible thread between faith and doubt. For younger generations, the digital world already feels natural, almost native. But that very comfort makes the situation more complex. As artists create boundless realities from their imaginations without limits or filters, how do we protect those who absorb them?

Perhaps our humanity lies in the desire to explore, to understand, to feel. Curiosity defines us. Yet blind belief can be dangerous. Art still comes from people, and people are not always stable, honest, or well. Somewhere in the fragile space between creation and manipulation, we must learn to stay awake.

The Responsibility of the Viewer

What do we actually seek in digital art, experience, wonder, or escape? Probably all three. Art has always had the ability to move us, to stir feelings we cannot name. But in the digital realm, it becomes harder to know what we are truly opening ourselves to.

We trust artists because we want to feel something, to be moved by what they share. Yet maybe we should be more cautious. When art becomes immersive, the viewer is no longer a passive observer but an active participant, a test subject stepping into another reality. It demands awareness. It demands boundaries.

I feel it myself, the resistance toward certain exhibitions. Sometimes I know instinctively when something will be too much, too intense, too closed in on itself. It is not about rejecting art, but about listening to intuition. Some works invite you in; others pull you in. And it is okay to say no.

When I see a work like The Song Trapper, I ask myself: what is the artist really trying to communicate, and why? Is the goal to move me, or to display their own mind? For me, technical brilliance is not enough. I need to feel intention, a trace of humanity behind the layers of sound, light, and code.

Maybe that is the viewer’s true responsibility: not to believe blindly, not to consume everything labeled as the future of art, but to stay alert. We open dimensions together, artist and viewer. And in that meeting lies both the beauty and the danger.

The Vulnerable Encounter

Perhaps all of this also comes from fear, not a negative fear, but one born of sensitivity. I often feel like a sponge, absorbing more than I can process. It feels risky to step into any reality created by someone else, not knowing how it might affect me. I need some sense of care, a hint of gentleness, a sign that there is thought behind the intensity.

Museums and institutions have a responsibility here. They should not only showcase what is possible, but also what is beautiful. They should search for the poetic within the digital, not only the sensory and the extreme. Art does not need to overwhelm to move us. Perhaps the digital art of the future is not about showing how far technology can go, but reminding us why we still need to feel.

I hope the digital realm will be used to create silence, beauty, and wonder, not just shock or sensory excess. In a time when everything can become an experience, perhaps calmness itself will be the most radical form of art.

Ingen død, bare RESPAWN” – digital utforskning av eksistens og teknologi. Nitja senter for samtidskunst, juni – september 2025.