This Artwork Should Never Have Been Shown at the National Autumn Exhibition

Originally published in Norwegian in Subjekt, October 26 2025 (click here)

I write this one week after the exhibition has ended.

But the work has not let go.

The provocation still sits in my body.

How do art institutions and critics handle trauma, the body, and ethics in public space?

Who actually decides where the line is — what is acceptable to show, and what is not?

Everything can be art, but not everything belongs in the National Autumn Exhibition.

I visit the Autumn Exhibition every year.

Yes, the show takes on important themes — art in all directions and expressions.

I know that the experience is rarely easy or comfortable, and I expect to encounter works that raise thoughts about war, women’s rights, life, and death.

But this year, I was shocked to encounter a work so direct, so unbearable in its expression.

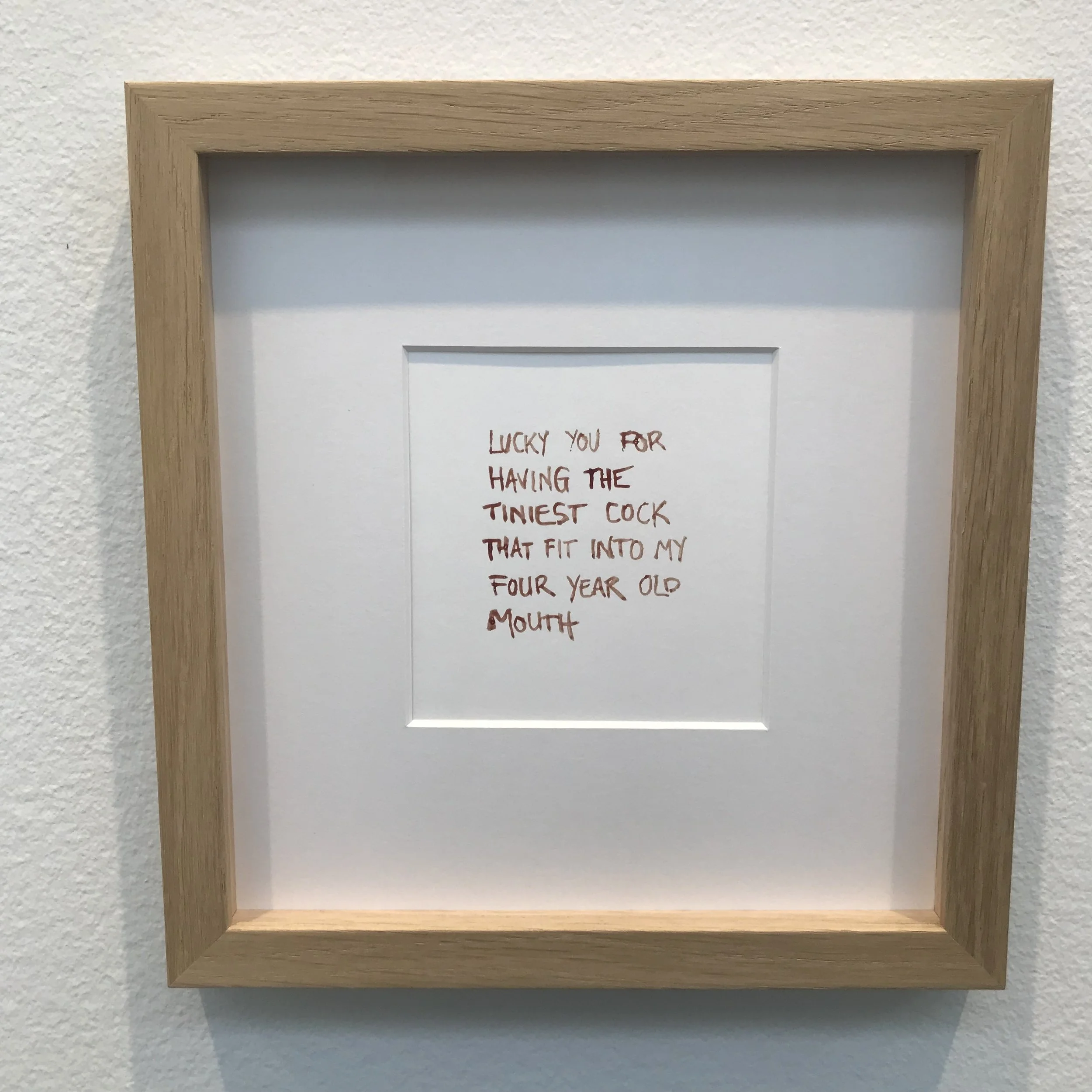

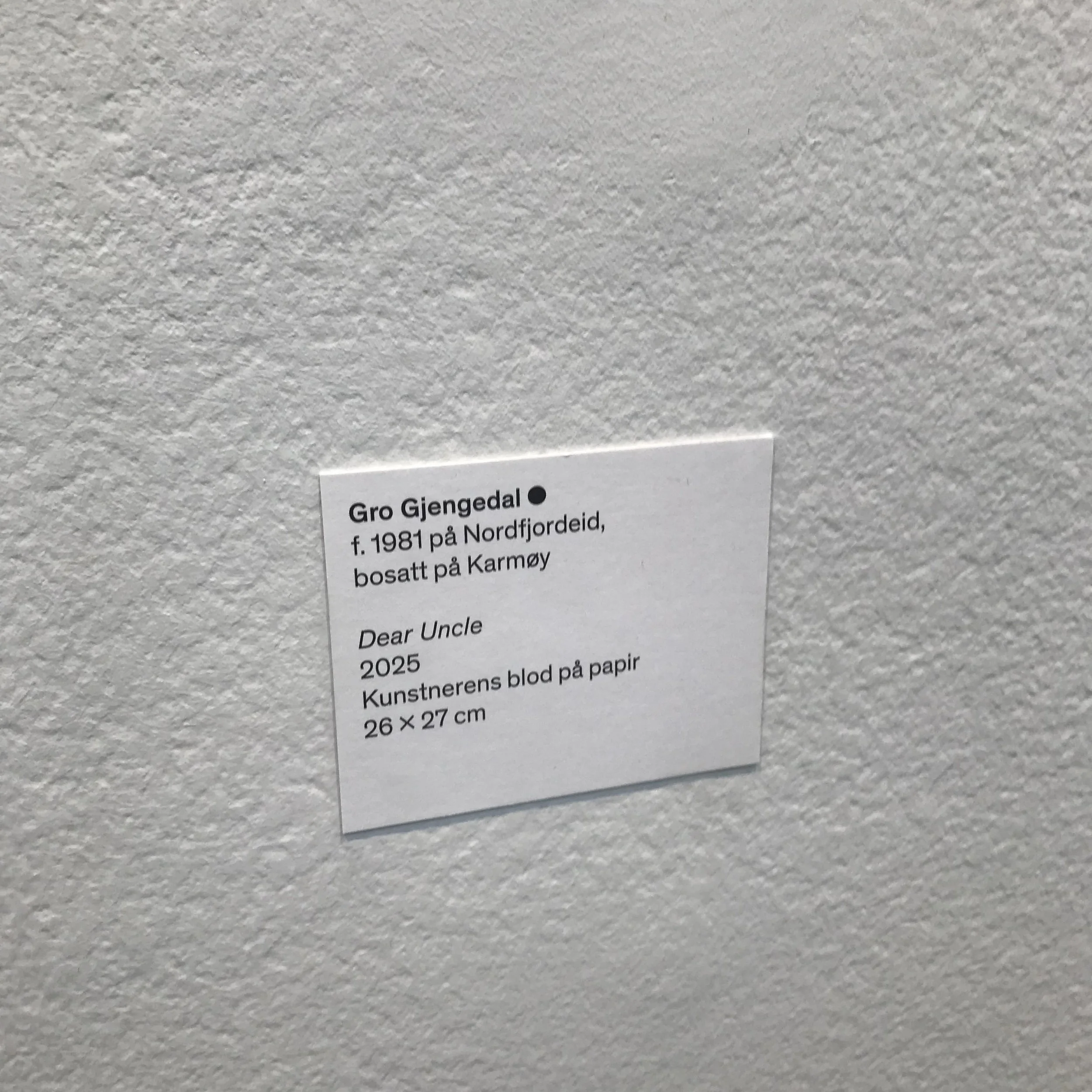

The work Dear Uncle by Gro Gjengedal describes, in explicit detail, a sexual assault on a child — written in the artist’s own blood — and exhibited at the National Autumn Exhibition.

There is no explanation, no context, no mediation.

Only a neutral biography. No reflection. No statement. Only silence.

When art addresses trauma, institutions have a responsibility for how it meets the public.

A child can read English.

A child cannot defend what it reads.

A child cannot grasp how serious this is, especially when the text stands there, framed, without context, in the state’s largest art exhibition.

I agree that art can process trauma, and that it is vital to give art the space to speak about painful things.

But art that works through trauma cannot reproduce the violation it addresses by being exhibited without explanation, safety, or care.

Everything can be art, but not everything should be shown.

When I asked about the work on Instagram, someone sent me an article that simultaneously described the exhibition as “relevant for children and youth.”

On the official website, there is no information about why the work was selected.

I wrote my comment as a simple question: Why is this work included?

I received no explanation.

That makes the question even more urgent:

Whom are we actually protecting — the art, the artist, or the children?

Art should be able to hold darkness.

But when institutions choose to display it, they must also carry the responsibility.

To hang up a text about the sexual abuse of a child without mediation is not to open a conversation; it is to let silence speak for itself.

But speak for whom? For the adult art-goer who moves on to the next room?

Who speaks for the child who can read but is given no explanation?

Who truly wishes to open this conversation inside a gallery space?

When I see two elderly women turn and whisper, “that’s grotesque,” I ask myself:

How would a child react?

Katia Maria Hassve (29)

Curator and writer, Master’s student in Art and Society at OsloMet